Women’s rights and patriarchal culture

Background

“Women face many challenges. Some of them result directly from traditional ideas of our community and from patriarchal structures. Some of them are exacerbated by these structures.” So says Cynthia Gwenzi, Gender Officer at Platform for Youth Development in Eastern Zimbabwe.

So are societies in Southern Africa patriarchal? The answer is yes, both pre-colonially and as a result of colonial history.

Oppression of women pre-colonial and colonial

African historian Jeff Guy postulated in 1990 that “the best way to understand the oppression of women in pre-colonial societies in southern Africa is to look at the production systems of the time…these societies were based on the appropriation of women’s labour”. Today, such materialist views – while not wrong – have been supplemented by a broader cultural history that restores women to a place as agents of action at all times. The icon for this is Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana, who was a powerful spiritual leader in the first anti-colonial struggle in Zimbabwe.

History shows that the colonial period massively reinforced the patriarchal system. One example from Zimbabwe was the de facto ban on young women (from the age of 12!) from entering into an arranged marriage. In pre-colonial times, women still had the possibility to run away with a lover over all mountains and thus come to a love marriage, which was subsequently regularised by the families. The colonial marriage law, however, stipulated that marriage and cohabitation “always” required the consent of the pater familias.

The history of colonial jurisprudence and administration, and also of the Christian mission, shows that the patriarchal ideas of colonial masters and missionaries repeatedly led to an alliance with particularly patriarchal interests of Africans. There is no doubt that many mission stations were a haven for young women seeking liberation from confining conditions. However, this liberation usually came at the price of subordination to the paternalism of the mission leaders.

Racist and patriarchal interpretations of “traditions”

The Zimbabwean social scientist Rekopantswe Mate recently wrote for the journal afrika süd about customary law as a racist and male-biased version of culture and tradition. According to Mate, this customary law is stable because religion, the education system and also the idea of “development” make it difficult for women even today to have an emancipated view of history.

Thus, customary law and moral condemnations often go hand in hand. To this day, women who escape male control are denied honourability and are often called “prostitutes”. Even moving to the city undermined a woman’s respectability. Women in the city therefore developed new codes of honourability – although it remains important to maintain contact with the family in the countryside. This example in particular shows well how new forms of patriarchal oppression emerged during the colonial period, as well as new forms of gender identities as lived by women.

Cultural debate under the sign of an anti-feminist backlash

Those who invoke culture still use one of the most significant weapons in the debates around women’s rights. NGOs representing women’s rights are portrayed by many, not least the ruling party, as a kind of Trojan horse with which the West is trying to maintain neo-imperialist control over Zimbabwe.

Feminists and their organisations, on the other hand, stress that women’s rights are indeed a Zimbabwean issue and also emphasise the role of these rights in Zimbabwean cultures. For example, they describe child marriages as a “harmful cultural practice”: not because they are necessarily rooted in local cultures, but rather because the patriarchal twisting of culture leads to excesses and then legitimises them as “traditions”.

An example of this was the introduction of laws against domestic violence in 2006. In the end, the women’s minister and civil society organisations prevailed. However, the debate was heated and loud, precisely because opposition politicians also joined the camp of the rejecting men’s guild. They said that women were not equal to men and that this “diabolical” law undermined the traditional status of men. For the state to interfere in the private affairs of men, they said, was against culture and tradition. Obedience in marriage and modest dress were promoted as traditional mechanisms against gender-based violence.

A missed departure?

The fact that such colonially overlaid currents of argumentation can persist to this day is actually astonishing. For in the 1970s, young women were invited to take on new roles as liberation fighters in the anti-colonial war. Many did – and many were disappointed. If this phase can be called a first phase of feminism in Zimbabwe, one must speak overall of a patriarchal backlash in the name of traditionalism and nationalism.

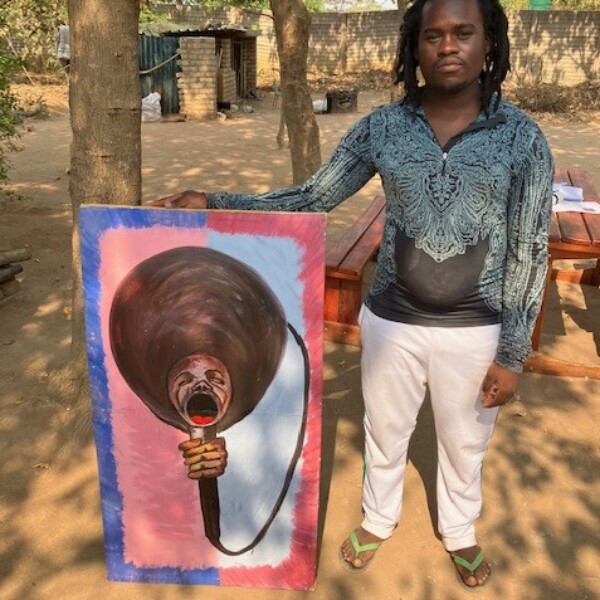

Women make history

Is there a way out of this backlash that could do without a critical examination of history? How else do women* defend themselves against those who invoke supposedly unshakeable traditions and defend patriarchal culture as “genuinely African”? With what awareness could the argument be refuted that the commitment to “fairness and equality … is anti-cultural, un-African and thus subversive”?

Rekonpatswe Mate points out that above all, the changeability of pre-colonial practices must be brought back into focus. That cultures and traditions should bring solutions to communities and not exist for there to be something that is absolute and unchanging. And she stresses that the lack of reflection on the influence of colonial rule weighs heavily. That is why a direct recourse to pre-colonial models that are supposedly vouched for today is not useful. Overall, Rekonpantswe Mate seems to have little hope that the conditions and a good space exist today for such a historical debate.

Broader alliances for a progressive culture

The fepa partner organisation Platform for Youth and Community Development, of which Cynthia Gwenzi is a member, takes a somewhat more positive view. Hope could come from the fact that the debate on women’s rights and culture is breaking through the usual binary political system in Zimbabwe. What started in 2006 with the debate on domestic violence is still evident today: politicians from all camps are publicly campaigning against gender-based violence. This opens up possibilities for civil society engagement and alliances among women, where discussions about progressive and emancipatory elements in traditions become possible. For Cynthia Gwenzi, this is one of the levers to fight for a progressive culture.

If you want to know more about the conditions for feminism and activism for women’s rights, visit our information page on Afrofeminism or follow us on Facebook for regular updates. Don’t forget to share the events and like fepa!

Appendix: Aspects of historical gender relations in Zimbabwe, based on Mate et al.

Pre-colonial gender relations

- Zimbabwe is ethnically and culturally diverse. Cultural identities have always been fluid: women in particular acquired multiple identities through marriage and moving.

- Patrilineality: for most ethnic groups, group membership, and thus access to resources or inheritance, runs in the patriline.

- Patriarchal: pre-colonial societies in Zimbabwe were male dominated.

- Women had a lower status. Extended families disposed of them as gifts to powerful people, as debt pawns or as surrogate wives. Women born into privileged circumstances tended to remain protected.

- Marriage “was a kinship-motivated and male-dominated social, economic and political alliance between or within kin groups”. In other words, marriage was not a pure love match, but was meant to serve families and communities.

- The “bride price” was an expression of these reciprocal relationships: Families exchanged valuable productive items with the wife’s parental family.

- Wives were given access to land and could earn their own income on it to feed the family. In Shona culture, they could also bequeath the income they had earned themselves.

Christianisation and colonialism

- Economically, women benefited from new opportunities until about 1930. Then, when the colonial economy needed more male labour, the workload for women increased sharply.

- At the same time, a colonial legal system was established that severely limited women’s opportunities. Men were given new ways to control women if that helped maintain control over men. In the context of a dual legal system, a patriarchal “indigenous” customary law solidified, claiming moral supremacy to this day.

- Christian communities offered new role models and femininities, characterised by “domesticity”. They propagated male-dominated forms of agriculture.

- Many women’s activities were lost: in pre-colonial times, women were still more common as craftswomen, as healers or midwives, or they also went hunting with men. Many of these areas were re-regulated to the detriment of African women.

- The “bride price” came in for sweeping criticism as a monetisation of marriage. In practice, however, it is still the prerequisite for a marriage that is considered respectable.