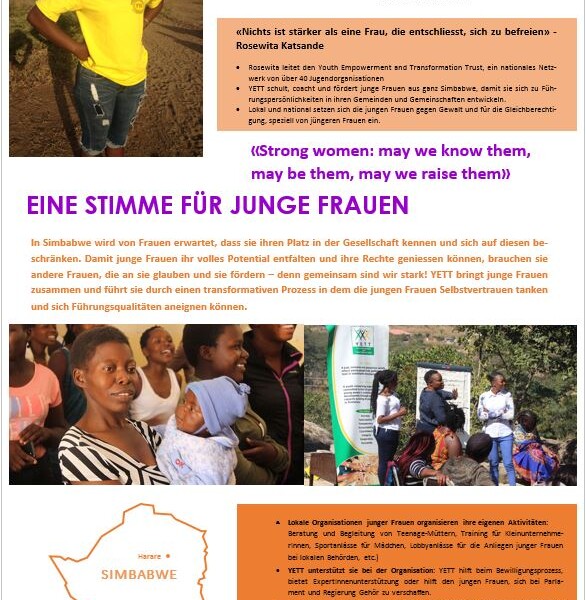

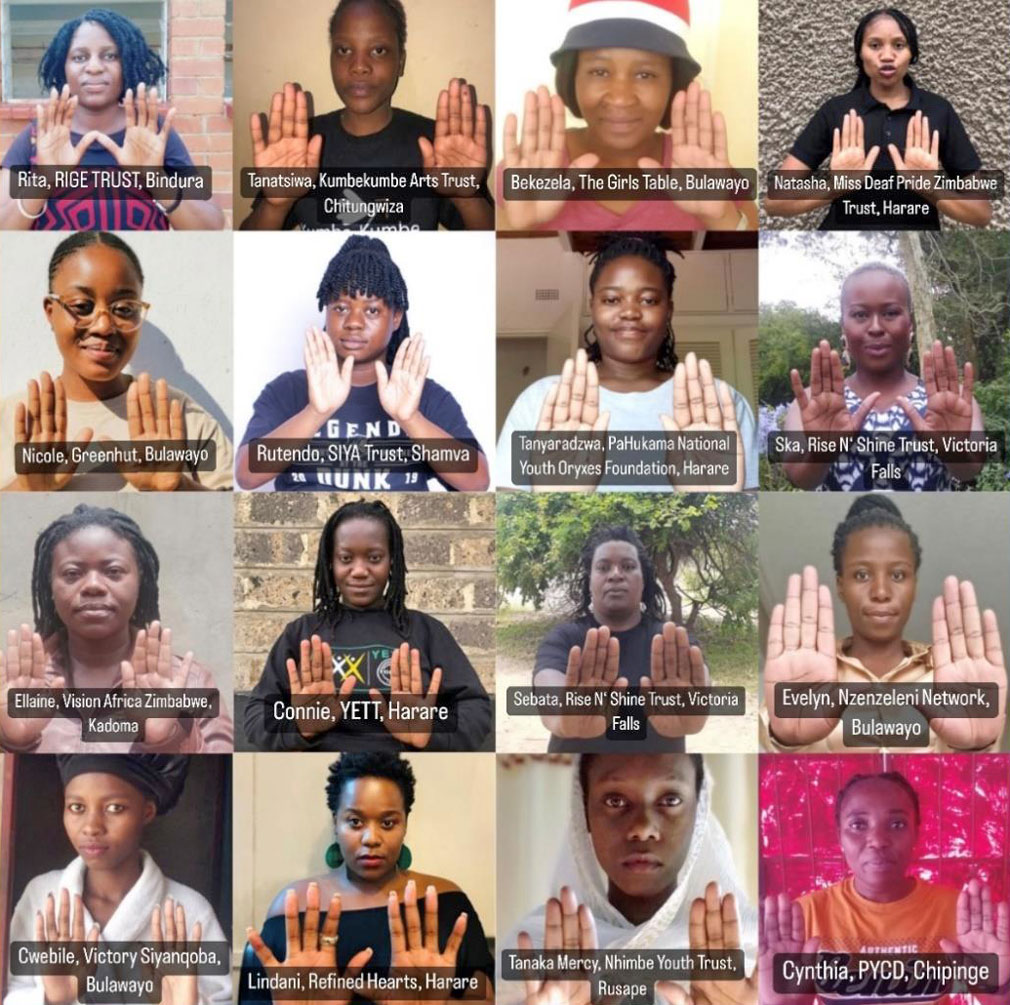

Advocacy

fepa is on the side of the disadvantaged. Our commitment is not only humanitarian, but also (development) political. We support those forces that stand up for social justice and democracy and stand up for them to be able to defend their rights. fepa therefore informs about the living environments of our partners and is specifically active when our solidarity can make a difference.